Natural Systems are Critical

Mohan Rao for Ekurhuleni: A Cityscapes Magazine Report • December 16, 2013

Large-scale urban design initiatives addressing the demands of dwelling and shelter often overlook critical issues such as site, neighbourhood and the natural environment

The transformation of cities is increasingly characterised by the notion of efficiency, by which I mean the tendency to maximise utility towards the regulation of urban capital. This theory of city making evaluates, restricts and recognises the role of various private commodities to the exclusion of public goods, notably the natural environment. Patterns of urbanisation in developing countries over the past six to seven decades shows a marked tendency where the understanding of these “public goods” remain two dimensional at best. Classical urban planning initiatives have invariably tackled settlement design through the consolidation and fragmentation of land, which is treated almost exclusively as an economic resource. All lands deemed unsuitable for development, notably marshes, wetlands, forests, hilly terrain, etc., are typically classified as non-developable land.

Two aspects of this approach to the management of public goods are important for our discussion: 1) the accepted notion of development, with its emphasis on the built environment and real estate, and 2) an approach to land that deems territory unsuitable for human settlement and development as wasteland, to be kept out of the realm of active programming and utilisation within an urban developmental framework. Together, these ideas have effectively rendered all natural capital in urban spaces as a liability and nuisance, rather than viewing it as a landscape rich with productive potential.

The attitudes of urban development professionals towards land and the natural environment have gone through two marked phases. Initially the emphasis was on what I call “land in the making”. This phase was marked by the aggressive legislation of natural systems that resulted in massive alterations to the landscape—through landfills, land-use modifications, reclamation projects, etc.—and seriously impacted regional natural ecology patterns. More recently, the emphasis has shifted to what I term “environment in the making”, where degraded and threatened ecological systems are cleaned, conserved and otherwise spruced up. The resultant landscape, whether real or virtual (in the sense that it may possibly be realised in the future), is then certified and presented as fit for receiving global capital. These distinct and tectonic shifts in attitudes towards the natural environment are crucial in understanding the evolving concept of cities: from development visions of cities as sites of social and economic mobility and catalysts of modernity, to the neoliberal visions of cities as strategic nodes for the operations of global finance. Environmental policies and action plans oriented towards beautification, development and engineered eco-restoration are merely idioms through which cities are positioning themselves in the global arena for capital accumulation through real estate. Rooted within this exploitation of natural resources and plasticity of environmental policies—which alter the very nature of relational value associated with natural resources and human habitation—is the closely related concept of informal settlements. Informal settlements are an urban necessity. Markers of continuous property creation in the city, they essentially represent property that is valued differently in the arc of a city’s history. Their erasure may be read as urban renewal, their appearance as urban decay. Typologically, they are hard to locate outside any urban centre, and—along with natural and human resources—form an essential infrastructure framework of the city. Natural systems, which conventional developmental policy views as a waste commodity, are often key sites for informal settlements. Myopic and superficial engagement with natural systems in larger planning frameworks often produces unstable and hazardous conditions affecting both the natural environment and human settlements established on them.

Remedial initiatives in this context often address mere beautification of natural systems and formalise settlements by dislocating them from the city fabric, typically by creating yet another environmentally sensitive zone, or wasteland. These initiatives, well intentioned or not, effectively create and/or further escalate deep fractures in the urban ecosystem. Environmentally, they delink and devalue natural resources and their crucial function within the city fabric. Socially, they exacerbate the unequal distribution and access of natural goods and services.

The improbable demands of capital-driven urbanisation, which are largely aimed at satisfying global investors, will continue to interlock ecological and social vulnerabilities in the urban terrain, and cut across—independently and interdependently—urban policies. This article, which discusses various strategies rooted in the Bangalore metropolitan region, is positioned in this flux. It emphasises an ecological understanding of natural systems and their capacities as landscape infrastructure. This article further looks at their ability to generate new relationships between the city and society, as well as function as a crucial support system for informal settlements by creating livelihood opportunities. My central argument is that natural systems are a critical dimension not only of the physical but also of the social production of urban space.

The Bangalore Context

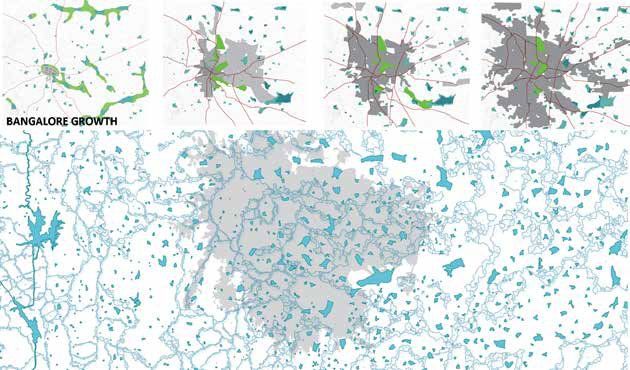

Located on the watershed of two principal river basins, the Bangalore region is part of the Deccan Plateau and presents dramatically varied terrains with the main ridge running north-northwest to south-southeast, effectively dividing Bangalore into two distinct topographical regions. This topography exhibits a radial pattern of drainage, distributing from the apex and flowing to the lower plains in dendritic and reticulate patterns. Bangalore, with its population of roughly seven million, is one of the few metropolitan cities located at more than 950 metres above sea level without any perennial source of water. The undulating topography, combined with a granitic geology, renders the region highly suitable for harvesting and managing water at both surface and sub-surface levels. Traditional settlements, which date over a thousand years, have used this potential extensively, creating a system of chain tanks and connected valleys as fertile ground for agriculture.

Though this linkage between natural system, resource and urbanisation has long been understood, even the most progressive planning processes have been unable to integrate them in a holistic and active manner. This is evident in the Bangalore Revised Master Plan 2015, which proclaims that the “green belt (composed of agricultural zone) plays a very useful role in limiting urban sprawl”. By confining the “green belt” as the physical boundary of the city, Bangalore has been allowed to develop in a radial urban form, completely ignoring the millennium-old natural history of the region. Derived from outdated and non-contextual planning theories, the “green belt” ideas have ended up severely undermining the performance and connectivity of natural systems in the region. This ecological framework, referred to as “bourgeois environmentalism” by some, has caused immense damage to the natural ecology of the region. It is estimated that of the 262 lakes identified in the Bangalore region in 1960, only 81 exist today—of these, only 34 are recognised as “live” lakes. While highlighting the plight of lakes, what the numbers do not reveal is the massive and irreversible destruction of valley networks, the very lifelines of the regional landscape. The valleys feed the lake system, regulate surface runoff, mitigate flooding, and sustain aquifers and wetland ecosystems. Bangalore’s planning paradigms, which have effectively turned their back on this natural framework, have resulted in, amongst other things, the severe depletion of ground water, increased flooding, loss of biodiversity, and increased urban heat islands. A similar pattern is echoed in other parts of India, as in Chennai, a city located along the Bay of Bengal, with the destruction of its lakes (or eris), a pattern of disappearance that became more permanent as the conversion of water to land becomes a strategy of urban expansion.

“Natural systems are a critical dimension not only of the physical but also of the social production of urban space“

Together with colleagues at Integrated Design, a Bangalore-based consultancy, I have been involved in framing the 2031 structure plan for the Bangalore region, which covers an area of 8005m2. The objective of the plan, known as BMR RSP 2031 and provisionally approved by the state government, is to provide the strategic policy framework for planning, management and development in the region without compromising on the ecological and environmental health of the land. While traditional planning exercises are driven by two-dimensional spatial characteristics of the land determined by administrative boundaries, the proposal took a radical route of defining land capacity based on the watershed character found in the region.

The definition of development was further refined and elaborated to include all aspects of development, both built and natural.

The Bangalore region is one of the most sensitive regions with respect to water resources. The city’s development has been totally driven by a reliance on the nearest totally driven by a reliance on the nearest perennial source, River Cauvery, located 108km on a lower elevation of 450 metres from the city. There are numerous water and environmentally sensitive issues that are vital to addressing the sustainable development of the Bangalore region. To enable an identification of these ecological parameters and allow them to be used positively for the development of the region, the BMR RSP 2031 engaged in a land capability analysis (LCA), a GIS-based decision-making method using multi-criteria parameters to arrive at a capability analysis. The output of the LCA is used to effectively address and incorporate the region’s natural resources in the physical and policy planning framework for development Land capability analyses are not new in urban and regional planning exercises. The normal procedure is to use a Cartesian grid

for assessment and grading of land parcels, although such a division, assessment and grading of land resource, whether urban or rural, fails to effectively recognise any of its natural characteristics. Acknowledging this aspect of conventional land capability analysis as a limitation and recognising the critical nature of the Bangalore region’s natural resources, specially the criticality of water resource, the random Cartesian grid has been replaced by a mini-watershed as the reference grid.

The LCA as employed by the BMR RSP 2031 recognises the critical nature of Bangalore’s natural resources to effectively allow the mapping of the sensitive ecological features as a prerequisite to identifying the development needs of the region. It employs the mini-watershed as the defining parameter for analysis and grading of land parcels. The LCA also grades the natural potential of land in concert with anthropometric parameters such as industry, transport, demographics, etc., to evolve a development potential matrix.

Ecosystem Services Infrastructure

Urban planning and design discourses have, of late, attempted to promote a conscious engagement with the natural environment, largely driven by external rating systems—the results are far from desirable. This could be attributed to first order political-economic demands, although it chiefly emerges out

of the understanding of capacities and performances embedded within these landscape systems, and the relations that they can nurture. Often, these systems are studied in isolation to their larger ecological and social-urban contexts, resulting in these systems being either objectified as mere protected corridors, or—worse—as beautified recreation pockets dotting the city fabric.

A conceptual shift is necessary, one that recognises and positions these landscape systems as networks and infrastructure critical to the larger ecological establishment. If one wants to successfully position natural landscapes and environmental systems within the seemingly improbable demands of contemporary urbanisation, a regimental shift is required, one that recognises that these landscapes must be evaluated not by their physical extent, but by their capacities and embedded performance. In short, it requires understanding the notion of ecosystems and their “services”. By definition, ecosystem services are the goods, functions and processes that are derived from the biosphere.

Being a member of the Adaptation Research Alliance, ARA (a global, collaborative effort to increase investment and opportunities for action research to develop/inform effective adaptation solutions) and an ARA Micro grantee, Integrated Design (INDÈ) was invited to organise a networking session at the Global Gobeshona Conference-2 (conference theme: exploring locally led adaptation and resilience for COP27). The networking session was titled ‘Situating Urban (City) Resilience within the City-Region’ and was held on 1 April 2022.

The online magazine SustainabilityNext carried an article by Benedict Paramanand titled “Has Fatigue Set into Civic Activism in Bengaluru?” The article caught my eye amidst the Covid 19 humdrum as I was looking for alternative news. I have been actively engaged in the debates around the (ill)growth and mis(management) of Bangalore for over two and half decades in my capacity as a professional planner straddling civic society, public policy circles and academia. The article revived in my mind some thoughts and suggestions that I articulate here. The attempt is not so much to answer the question, as it is to understand the shortcomings and limitations of civic activism in steering the complex politico-socio-economic and cultural layers that make up a vast conglomeration like Bengaluru. A disclaimer here merits mention. The premise that no individual stakeholder, public or private, has the knowledge and resources to tackle the wicked problems underpins successful governance arrangements. What this premise implies, by extension is that all stakeholders – public or private – have limitations. Civic Society (CS) is one amongst the numerous stakeholders that have a role – by no means a lesser one- to play. Yet, there are limitations to this role. While these limitations are embedded in the very nature of operation of the CS, there are conscious ways and means of overriding some limitations to move towards a larger impact. Bridging limitations is a critical need. Much of what I articulate while contextual to Bengaluru, perhaps holds true for civic activism across domains and geographies. To begin with, a critical question requiring reflection is the difference between civic activism and the much advocated (in (good) governance debates) Civic Society Organisation (CSO) engagement. These generally get clubbed in one category – while in theory and practice, that is not the case and therein lies the first limitation. Activism defined as direct vigorous action especially in support of or, in opposition to, one side of a controversial issue is willy-nilly an act of reaction. Reaction often leaves little space for taking distance and exploring the systemic cause of the challenge – the challenge itself sets the agenda. In contrast a proactive engagement of the civic society, through progressive partnerships while also triggered by a challenge is different in that the challenge is anticipated and therefore the agenda is set by civic society themselves. In Bengaluru, protests against the state-imposed flyover (# steelflyoverbeda ) and elevated corridors (# TenderRadduMadi ) is an example of the former. In contrast, the long-standing work on the ward committees which has seen some traction in the recent past – albeit slow and tardy – is an example of the latter. Having started as a proactive CSO engagement, the movement for neighbourhood planning and governance through ward committees (# NammaSamitiNamagaagi ) in the recent past has bordered on being reactionary, thereby hinging on activism. Although an ‘always proactive approach’ is not possible, given the capacity of our government to spring surprises, it is critical that the CS begins to move towards a proactive stance. There will always be a non-uniform interplay between being reactive and proactive. A second limitation, linked to the first, is the lack of capacity of the CS to act on relevant and practical evidence. This will require the CS to open their doors and develop progressive partnerships, including partnerships with policy makers, professionals (note that I do not use the word experts) and academia. An all-time reactionary mode of operation allows neither for collaborations nor evidence. Evidenced advocacy and conversations require domain knowledge (experienced domain knowledge is even better) which can facilitate knowledge production and mobilization. Activism hinges on passion (amongst other drivers) which is not the same as domain knowledge and knowledge mobilization. Both passion and domain knowledge have a role, yet the two can neither replace each other nor should be confused. Rather, passion that pivots on evidence and knowledge is a double-edged sword, one that has the capability to steer reactionary behavior to an informed proactive engagement. Such a move will serve to, over a period of time, course correct policies that are currently influenced by dominant political structures, electoral volatility and elite capture, as against being evidence based. A third limitation that needs consideration is the nature, purpose, goal and objective of the civic society coalition/group. Most often mobilisation is around a seemingly common purpose, goal and objective. For instance, groups that coalesced against large infrastructure projects as mentioned above or the demand for footpaths and public transit (# BusBhagyaBeku ) and sub-urban rail (# chukuBukuBeku ) are not homogeneous. It is often a mixed bag as against an imagined and perhaps desired integrated unit. Underpinning this pursuit of collective goals and objectives are individual desires, identities (which in themselves are multiple), beliefs, perspectives and previous experience, all of which are critical drivers, often leading to fragmented voices. This fragmentation notably, also derives from the inability to use evidence or domain knowledge. Elitist Activism Furthermore, activism in itself is and can be elitist. When linked to high levels of access it can be potentially hampered by what is referred to as ‘elite capture’. There are two types of activism: elite activism stemming from mobilization of charismatic individuals capable of getting their voice heard. Mass activism, in contrast, is where the general public, the haves and the have-nots, mobilize collectively. The two are not mutually exclusive, although both are critical. Barring a few occasions, Bengaluru’s activism has been elitist with a few voices that can access public policy corridors and therefore get heard. Consequently, consciously or unconsciously there is a leveraging of public policy for personal or limited gains (to a neighbourhood or a community). Activism is a luxury that not everyone can afford. Those who can afford it have a dual responsibility of using it to build bridges by roping in knowledge and experience on one hand and ensuring inclusion by creating spaces and opportunities for mass activism, on the other. The current modus operandi lacks on both counts. These shortcomings have led to what is being referred to as limited success, although limited from whose lens and success for whom is an additional enquiry, one that merits a separate post. What I do concur with is that at best the city has seen some cosmetic changes. Let me take the same two examples the article uses to demonstrate a going forward beyond cosmetic progress. First are the lakes in Bangalore that have seen a fair bit of activism. In many neighborhoods, thanks to the many charismatic residents, lakes have been claimed as better maintained natural resources. But for the initiatives of a few citizens, many lakes would have morphed into real estate projects. Yet, the same groups have done little to engage the larger neighborhoods to ensure that these natural resource ‘spaces’ become public ‘places’ for the neighborhood and the city. This would require a proactive engagement in identifying the larger neighborhood and the numerous linkages – backward and forward – that this neighborhood has had and can nurture with the lakes as public places. The second is the Tender Sure roads pioneered by Bengaluru. The implementation of Tender Sure roads is progressing incrementally moving from a pilot in the city core to radiating outwards in various directions. Putting aside the debates on the efficacy of the design as well as the appropriateness and relevance of the idea, the incremental implementation is marked by controversies on the criteria to shortlist roads such that both the visibility of and utility to the neighborhood and the city can be maximized. This too has not happened. Both these examples offer a critical insight: that the activism (and the few instances of engagement) has not translated into a thinking city. Changes are still hovering around the thinking individual. The transition to a thinking city is an emerging imperative, one that demands systemic change along various dimensions, some of which I have discussed above. To sum-up, sustained and big bang change as against cosmetic and incremental change is the need of the hour. It requires at the outset, one, more proactive engagement and less reactive activism; two, passion combined with experienced domain knowledge to trigger evidenced advocacy and change; and, three a less fragmented approach through creating meaningful spaces for mass activism along with the existing elite activism that the city has. While there may be numerous ways to act on these three, the Ward Committee space offer a ready platform for proactive action, evidence-based advocacy and wider participation. Arguably, this space is rife with political contestations and may seem a daunting challenge, yet, an engagement within this space is a surer foot forward. Clearly, there is a passion amongst Bangalore’s elite to be part of something bigger and this is a moment to be seized.