Lessons in Sustainable Hydrology from an Old Indian Empire

Kimberley Mok for TreeHugger • November 16, 2007

Imagine my delight when I got to interview Bangalore-based designer Mohan Rao of Integrated Design (ID), whose small, multidisciplinary firm is now working on a sustainable restoration scheme of the reservoirs around the small but legendary town of Hampi, in the Indian state of Karnataka – a World Heritage site and certainly one of most magical places on the subcontinent and where the surrounding ruins mark the historical location of the fourteenth-century South Indian empire of the Vijayanagara.

Firms such as Rao’s in India are interesting because they present alternative methodologies in an already-blossoming sustainability movement in India – synthesizing and building upon traditional/historical experiences with modern, holistic know-how to address problems of conservation and heritage preservation.

In a nation where each new, big hydrological dam spawns more environmental and social problems than it solves, Rao is busy challenging large-scale methods of resource management and hydrological restoration with alternative, sustainable and small-scaled approaches of revitalization in Hampi. Rao also recently finished up some disaster management consulting on the Nicobar Islands and an urban habitat project in Morocco.

Treehugger: Could you give us a little information on your background and why you started Integrated Design?

Mohan Rao: I am originally from Bangalore, but I’ve worked and travelled around a lot. I received the conventional bachelor’s in architecture and a master’s in landscape from School of Planning & Architecture at Delhi. After a few years of working in architecture, I was rather disillusioned with it and started ID as a conventional landscape design firm – but also quickly became disillusioned with that as well. That’s because in conventional design, everyone has strict lines between architecture versus landscape versus engineering versus site management that you are not supposed to cross. That’s why ID is a little harder to pigeon-hole because we do it all – we do a little bit of architecture, a little bit of landscape, some resource and site management and hydrology here, and sustainable restoration and consulting there.

TH: What is your focus now in the context of projects that you are currently involved with?

Rao: We have a few points of concentration now: one of them is water; another is site management, especially on smaller acreages (usually two to three); and another focus is the role of sanitation cycles. The last few years we’ve gotten involved with on-site heritage restoration and resource management at the city level.

TH: Could you describe the Hampi heritage restoration initiative and what is ID’s role within that?

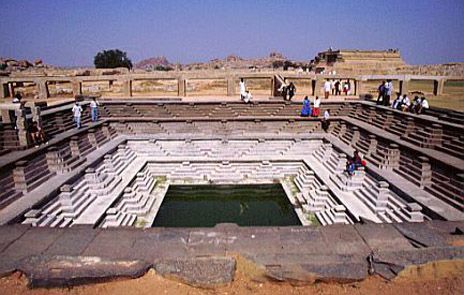

Rao: Though I’ve been working in some capacity with the initiative for the last 20 years, it is the only last five or six years we became formally involved with the archaeological survey taking place there. We were asked to do the landscaping for the gardens, which attract a great number of tourists annually – but eventually it became more than just a superficial greening when we got really interested in investigating how the old empire of the Vijayanagars (1336-1646 AD) dealt with water issues in what was a very dry area. For the last 300 years the River Tungabhadra was never touched – so how did the empire get its water? So we started learning about traditional ways of rainwater harvesting and storage and came up with some very interesting findings.

We unearthed small percolation pits, detention ponds, swales and valleys which were all part of a system ensuring a year-round supply of water in the historical city of Hampi, which had about 600,000 inhabitants at that time. We were working to understand how the water supply system worked, with wells and pipes all working energy-free and integrated that awareness into our efforts.

TH: How do all these lessons from Hampi apply to current water scarcity issues in the region’s cities?

Rao: Well, today’s Hampi offers many lessons for huge living cities such as Bangalore. Over the last five years, globalization has overtaken Bangalore, with obvious things such as traffic congestion increasing eight to tenfold. It’s one of the few cities in the world that has no sizable natural water source nearby and for the last 300 to 400 years it was necessary to build small water tanks at 50 to 100 acres in size. Lakes in Bangalore used to number around 200, but none of them were large enough to satisfy Bangalore’s present demand and right now water is being pumped from 100 kilometres away. So you have these water issues that not only find their roots in history but also in the geography of the region.

Lake revitalization is usually seen as an engineer’s domain: taking out muck, building retaining walls and beautifying it with gardens. However, instead of addressing the real problem, which is not the lake itself but the quality of runoff, land use, management and so on – you can start treating it as a natural resource which has a larger bearing on the environment – it’s not just something on the map – and start from there instead.

TH: What specific measures and methods did you employ then?

Rao: We started by cleaning up and controlling the inflow using passive and biotic methods, using plants that will clean up the water, for example – as the inflow determines whether the lake will live or die (due to influx of pollutants, organic matter, etc.). We did not use any kind of machinery, and this is basic hydrology and traditional wisdom across the world.

Next, using micro-catchments are the way to go, as they are cheap, need no energy to run and don’t displace people or submerge forests. Everyone wants development but that doesn’t mean you accept every technology without question.

Being a member of the Adaptation Research Alliance, ARA (a global, collaborative effort to increase investment and opportunities for action research to develop/inform effective adaptation solutions) and an ARA Micro grantee, Integrated Design (INDÈ) was invited to organise a networking session at the Global Gobeshona Conference-2 (conference theme: exploring locally led adaptation and resilience for COP27). The networking session was titled ‘Situating Urban (City) Resilience within the City-Region’ and was held on 1 April 2022.

The online magazine SustainabilityNext carried an article by Benedict Paramanand titled “Has Fatigue Set into Civic Activism in Bengaluru?” The article caught my eye amidst the Covid 19 humdrum as I was looking for alternative news. I have been actively engaged in the debates around the (ill)growth and mis(management) of Bangalore for over two and half decades in my capacity as a professional planner straddling civic society, public policy circles and academia. The article revived in my mind some thoughts and suggestions that I articulate here. The attempt is not so much to answer the question, as it is to understand the shortcomings and limitations of civic activism in steering the complex politico-socio-economic and cultural layers that make up a vast conglomeration like Bengaluru. A disclaimer here merits mention. The premise that no individual stakeholder, public or private, has the knowledge and resources to tackle the wicked problems underpins successful governance arrangements. What this premise implies, by extension is that all stakeholders – public or private – have limitations. Civic Society (CS) is one amongst the numerous stakeholders that have a role – by no means a lesser one- to play. Yet, there are limitations to this role. While these limitations are embedded in the very nature of operation of the CS, there are conscious ways and means of overriding some limitations to move towards a larger impact. Bridging limitations is a critical need. Much of what I articulate while contextual to Bengaluru, perhaps holds true for civic activism across domains and geographies. To begin with, a critical question requiring reflection is the difference between civic activism and the much advocated (in (good) governance debates) Civic Society Organisation (CSO) engagement. These generally get clubbed in one category – while in theory and practice, that is not the case and therein lies the first limitation. Activism defined as direct vigorous action especially in support of or, in opposition to, one side of a controversial issue is willy-nilly an act of reaction. Reaction often leaves little space for taking distance and exploring the systemic cause of the challenge – the challenge itself sets the agenda. In contrast a proactive engagement of the civic society, through progressive partnerships while also triggered by a challenge is different in that the challenge is anticipated and therefore the agenda is set by civic society themselves. In Bengaluru, protests against the state-imposed flyover (# steelflyoverbeda ) and elevated corridors (# TenderRadduMadi ) is an example of the former. In contrast, the long-standing work on the ward committees which has seen some traction in the recent past – albeit slow and tardy – is an example of the latter. Having started as a proactive CSO engagement, the movement for neighbourhood planning and governance through ward committees (# NammaSamitiNamagaagi ) in the recent past has bordered on being reactionary, thereby hinging on activism. Although an ‘always proactive approach’ is not possible, given the capacity of our government to spring surprises, it is critical that the CS begins to move towards a proactive stance. There will always be a non-uniform interplay between being reactive and proactive. A second limitation, linked to the first, is the lack of capacity of the CS to act on relevant and practical evidence. This will require the CS to open their doors and develop progressive partnerships, including partnerships with policy makers, professionals (note that I do not use the word experts) and academia. An all-time reactionary mode of operation allows neither for collaborations nor evidence. Evidenced advocacy and conversations require domain knowledge (experienced domain knowledge is even better) which can facilitate knowledge production and mobilization. Activism hinges on passion (amongst other drivers) which is not the same as domain knowledge and knowledge mobilization. Both passion and domain knowledge have a role, yet the two can neither replace each other nor should be confused. Rather, passion that pivots on evidence and knowledge is a double-edged sword, one that has the capability to steer reactionary behavior to an informed proactive engagement. Such a move will serve to, over a period of time, course correct policies that are currently influenced by dominant political structures, electoral volatility and elite capture, as against being evidence based. A third limitation that needs consideration is the nature, purpose, goal and objective of the civic society coalition/group. Most often mobilisation is around a seemingly common purpose, goal and objective. For instance, groups that coalesced against large infrastructure projects as mentioned above or the demand for footpaths and public transit (# BusBhagyaBeku ) and sub-urban rail (# chukuBukuBeku ) are not homogeneous. It is often a mixed bag as against an imagined and perhaps desired integrated unit. Underpinning this pursuit of collective goals and objectives are individual desires, identities (which in themselves are multiple), beliefs, perspectives and previous experience, all of which are critical drivers, often leading to fragmented voices. This fragmentation notably, also derives from the inability to use evidence or domain knowledge. Elitist Activism Furthermore, activism in itself is and can be elitist. When linked to high levels of access it can be potentially hampered by what is referred to as ‘elite capture’. There are two types of activism: elite activism stemming from mobilization of charismatic individuals capable of getting their voice heard. Mass activism, in contrast, is where the general public, the haves and the have-nots, mobilize collectively. The two are not mutually exclusive, although both are critical. Barring a few occasions, Bengaluru’s activism has been elitist with a few voices that can access public policy corridors and therefore get heard. Consequently, consciously or unconsciously there is a leveraging of public policy for personal or limited gains (to a neighbourhood or a community). Activism is a luxury that not everyone can afford. Those who can afford it have a dual responsibility of using it to build bridges by roping in knowledge and experience on one hand and ensuring inclusion by creating spaces and opportunities for mass activism, on the other. The current modus operandi lacks on both counts. These shortcomings have led to what is being referred to as limited success, although limited from whose lens and success for whom is an additional enquiry, one that merits a separate post. What I do concur with is that at best the city has seen some cosmetic changes. Let me take the same two examples the article uses to demonstrate a going forward beyond cosmetic progress. First are the lakes in Bangalore that have seen a fair bit of activism. In many neighborhoods, thanks to the many charismatic residents, lakes have been claimed as better maintained natural resources. But for the initiatives of a few citizens, many lakes would have morphed into real estate projects. Yet, the same groups have done little to engage the larger neighborhoods to ensure that these natural resource ‘spaces’ become public ‘places’ for the neighborhood and the city. This would require a proactive engagement in identifying the larger neighborhood and the numerous linkages – backward and forward – that this neighborhood has had and can nurture with the lakes as public places. The second is the Tender Sure roads pioneered by Bengaluru. The implementation of Tender Sure roads is progressing incrementally moving from a pilot in the city core to radiating outwards in various directions. Putting aside the debates on the efficacy of the design as well as the appropriateness and relevance of the idea, the incremental implementation is marked by controversies on the criteria to shortlist roads such that both the visibility of and utility to the neighborhood and the city can be maximized. This too has not happened. Both these examples offer a critical insight: that the activism (and the few instances of engagement) has not translated into a thinking city. Changes are still hovering around the thinking individual. The transition to a thinking city is an emerging imperative, one that demands systemic change along various dimensions, some of which I have discussed above. To sum-up, sustained and big bang change as against cosmetic and incremental change is the need of the hour. It requires at the outset, one, more proactive engagement and less reactive activism; two, passion combined with experienced domain knowledge to trigger evidenced advocacy and change; and, three a less fragmented approach through creating meaningful spaces for mass activism along with the existing elite activism that the city has. While there may be numerous ways to act on these three, the Ward Committee space offer a ready platform for proactive action, evidence-based advocacy and wider participation. Arguably, this space is rife with political contestations and may seem a daunting challenge, yet, an engagement within this space is a surer foot forward. Clearly, there is a passion amongst Bangalore’s elite to be part of something bigger and this is a moment to be seized.